Commonwealth of Learning, Knowledge Series, A Topical Start-up Guide to Distance Education and Practice Delivery

PDF for download on CoL website is available here.

Caren Watkins, Dr. Jutta Treviranus, Dr. Vera Roberts

Inclusive Design Research Centre

September 2020

Abstract

Globally, children with disabilities are disadvantaged in the school environment. Some studies have shown that they are also disproportionately represented among out-of-school children (Saebones et al., 2015). Inclusive Design for Learning provides a means to address this crisis of exclusion of persons with identified and unidentified disabilities, which may be permanent or episodic. Through the individualisation and adaptation of learning materials enabled by open education practices and the flexibility of digital resources, excluded or struggling learners can be included, to the benefit of all learners. This Knowledge Series paper introduces the dimensions of inclusive design as it applies to learning and focuses on the design of diverse learning experiences to help optimise learning opportunities for all learners.

Introduction

Education is a fundamental human right; it should not be viewed as an industry. Educators know that every student is unique and variable, that there is no average student. Yet most school systems standardise education. Society’s greatest asset is human diversity. Our ability to respond to the unexpected, innovate and evolve is fuelled by our diversity. Inclusive Design for Learning is a practice that supports optimising unique human differences and creating the conditions for a diverse (yet cohesive) global learning community of lifelong learners. This benefits not just struggling students but all students.

In addition to the complex task of providing education to learners who are no longer in classrooms, the COVID-19 pandemic has exposed and amplified the inequities and barriers in education. The inequities are not new or the result of social distancing and other public health measures. The pandemic has highlighted the lack of flexibility and adaptability within education systems, causing some students to feel the harm more than others.

Inclusive Design for Learning is not about services or products to “solve” learning deficits. Inclusive design is a practice, a culture — and likely, for many, a culture change. Humans are designing systems daily and continuously in many ways; as educators, we are designing curricula, education management systems and learning environments. Designing inclusively begins with the understanding that there is no definitive checklist or one-size-fits-all solution. The goal of Inclusive Design for Learning (IDfL) is to support diversity and variability by co-creating “one-size-fits-one” learning experiences within an integrated learning environment. Inclusive Design for Learning leverages the global open education community to co-create and share learning options to meet the full spectrum of student needs.

Situating Inclusive Design

Several practices support equitable education. Among them are Universal Design for Learning (UDL) and accessibility. UDL provides principles for preparing a learning environment that is designed for diverse abilities based on “scientific insights into how humans learn” (CAST, 2020; Wikipedia contributors, 2020b). Many countries have adopted accessibility regulations and policies, including Web accessibility guidelines that provide a checklist of testable criteria for compliance.[1]

Inclusive Design for Learning differs in that:

- it is a process, not a set of criteria;

- it addresses any human difference marginalised by standard designs;

- in the design process, it engages the individuals whose needs are not met; and

- it is ongoing to respond to the complex, changing context of education.

UDL, accessibility and IDfL are complementary in that UDL and accessibility provide a baseline or range of options and technical conditions for the practice of inclusive design.

Inclusive Design Dimensions and Learning

Through over 25 years of applied research, the Inclusive Design Research Centre (IDRC, 2020) operationalised the concept of inclusive design as three dimensions (Treviranus, 2018). These dimensions guide the practice of inclusive design across many domains, including learning.

- All students are unique and variable. As educators, we help students discover, explore and value their own uniqueness, optimise their individual skills and differentiate themselves. This is the case for all students and is done within an integrated learning environment.

- The process of designing education should itself be inclusive. Does the learning process engage perspectives that have been marginalised, and thereby support a multi-perspectival view? Does the process recognise the value of mistakes and uncertainty, and encourage students to take risks and understand the value of vulnerability? Does the learning process support teamwork, collaboration and knowledge sharing? Do the learning activities contribute to a purpose beyond evidence of learning? Ultimately, a cohesive multi-perspectival community of learners is engaged in actively extending the boundaries of knowledge.

- The education practice strives to create culture change that benefits all within the context of changing complex adaptive systems that make up our world. Are full social / environmental / economic impacts considered locally, globally and long-term? Is the education practice avoiding linear, simplistic and static thinking?

Benefit for All

Designing with learners and educators who are marginalised in current systems benefits everyone within the system. It leads to greater creativity and a system that can respond to change, and it costs less in the long term. The disruption to the status quo brought about by the pandemic may give us an opportunity to rethink our priorities and create a more generous system that includes learners that have been marginalized and serves us when everyone is struggling. When we make room for our diversity, we find a deeper commonality. We are all fragile and vulnerable; we all make mistakes; we all have inner strengths and weaknesses. When we recognise these commonalities, we can create a dynamically resilient society that serves us when we are vulnerable.

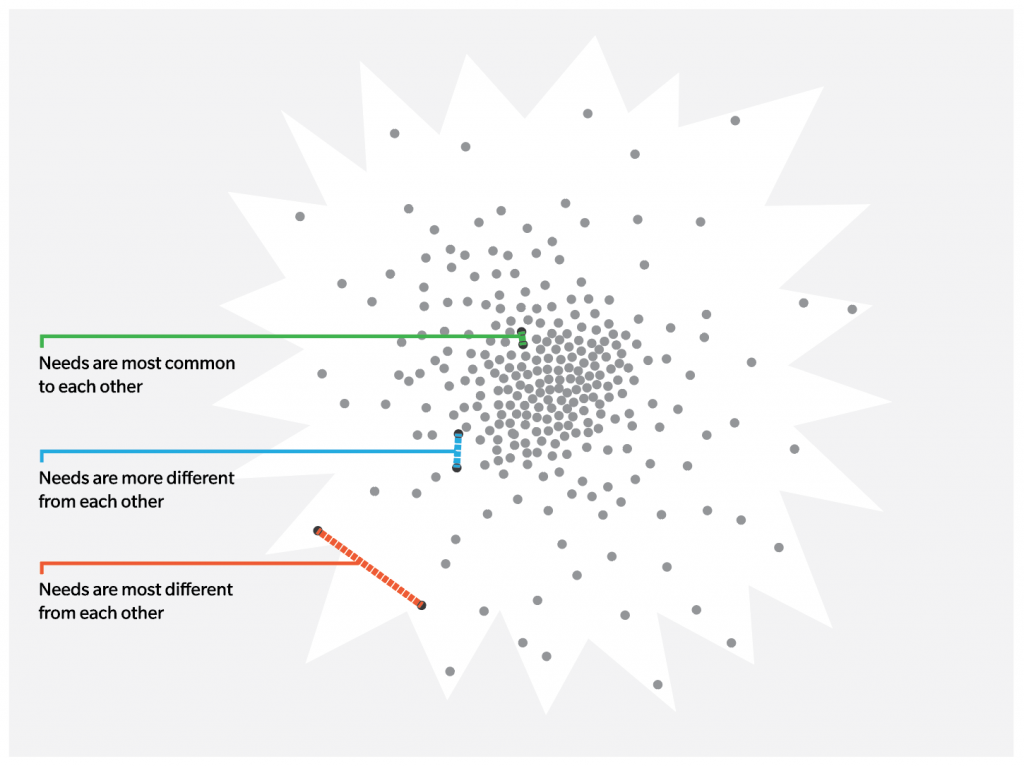

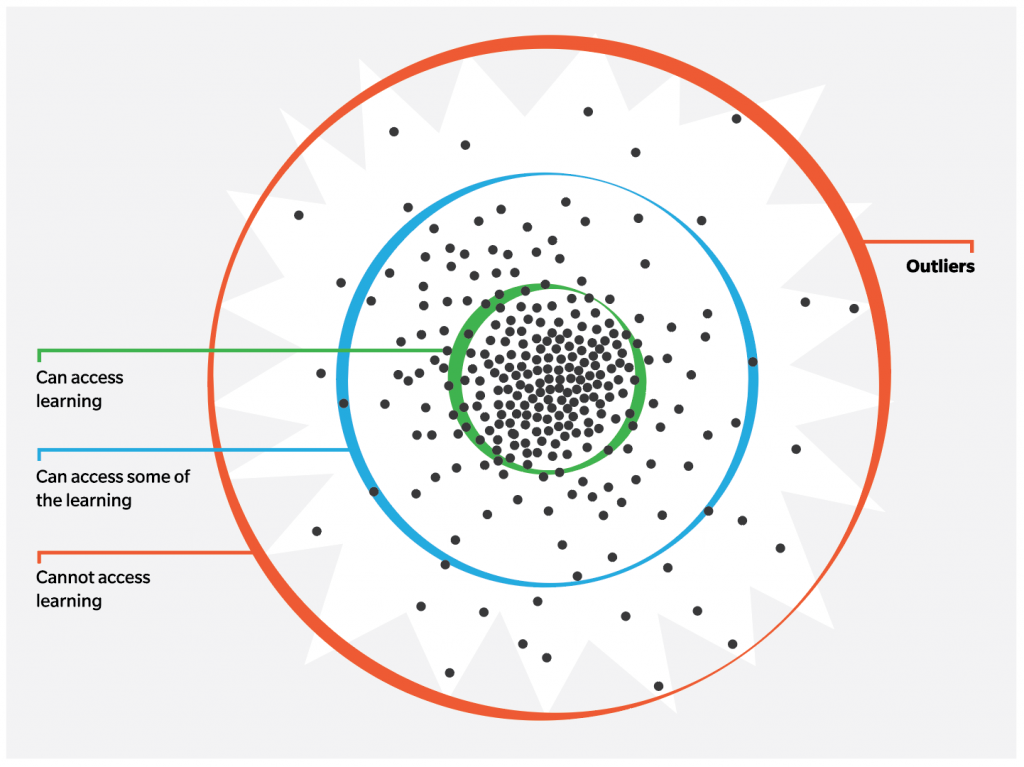

The benefit of inclusive design and the progress toward greater inclusion can be illustrated in data patterns. If we take all the learning needs of a classroom and plot these on a multivariate scatterplot, we will see something like the “starburst” scatterplot in the figures below. The needs in the centre will be closer together, while the needs outside the centre will be further and further apart, meaning they are more and more different from each other (Figure 1). According to Pareto’s 80/20 rule (Wikipedia contributors, 2020a), about 80 per cent of the needs will be clustered at the centre, taking up about 20 per cent of the space (Figure 2). The other 20 per cent will spread out from this centre to take up about 80 per cent of the space.

Because of our traditional approaches to design, research and assessment, the needs at the centre will be well met, the needs away from the centre will be inadequately met, and the needs at the edge will not be met. Unless we employ inclusive design, this means that anyone whose needs stray from the centre at any time will face compounding barriers.

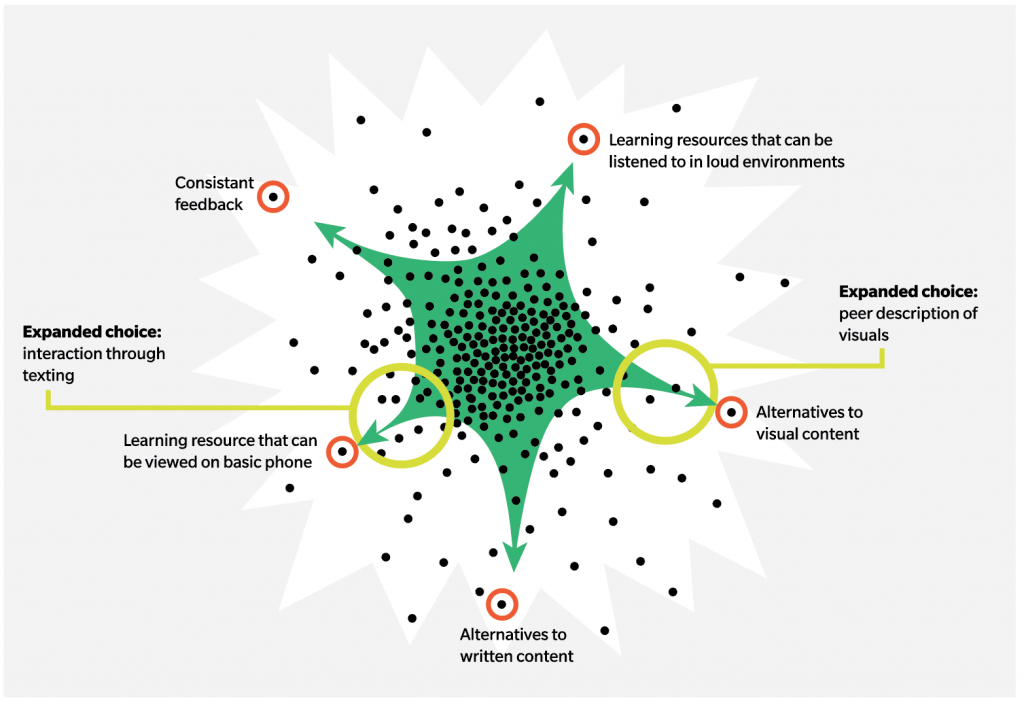

It is out at the margins of this human scatterplot that we find innovation or creative new approaches and detect the weak signals that indicate the cracks in our systems. This is the vulnerable edge that the pandemic has painfully revealed. The more we design our learning experiences to address the needs out at that edge, the more our education system will be able to adapt to change and the unexpected (Figure 3). Every step that was taken prior to the pandemic to address the needs further from the centre (e.g., digital resources in multiple formats, captioned videos, multilingual translation, open educational resource libraries) benefits everyone during this crisis, when we all face barriers. Rubrics and a predetermined set of steps and criteria usually don’t cover the complex and entangled unmet needs of marginalised learners and their unpredictable contexts, or the unpredictable situation we all now face.

Support with Choices

By focusing on the range of needs rather than the average need, we create a breadth of choices that benefit students who have complex and diverse minority needs, as well as learners with majority needs who are experiencing situational or temporary barriers (e.g., injury, displacement, crisis). Self-determination and self-knowledge are nurtured by engaging students in identifying their needs and helping them to make informed choices.

Most learning content is in a digital format at some stage of its development. Digital content is important not only because so much learning has moved to online formats amid the COVID-19 pandemic, but also because it is amenable to adaptation for different modes of interaction — for example, spoken words can be transformed to digital text, then to Braille; font can be enlarged; contrast or colour can be enhanced; text can be simplified or translated into other languages; and it can be read aloud by text-reading software. The goal is to select or create a range of learning resources that give learners options, and to provide the opportunity for learners to discover, express and explore how they can optimise their own learning. When collectively creating the pool of choices, we need to continuously ask: Whose needs are not met? Who is still excluded?

Preparing Students for the Future

Current students are clearly encountering a different reality than prior generations have faced. Many disruptive influences can and are changing the future of work and what will be demanded of them. There is a growing appreciation of the importance of human difference over standardisation and conformity, co-operation over competition, and active lifelong learning over passive learning. There is also an evolving understanding of equity as being more than measurable and standardised equal treatment at the expense of valuable student diversity.

In response to this uncertainty, there has been a movement toward more active, experiential, collaborative and self-directed learning. Problem-based learning[2] and inclusively designed learning tools such as accessible PhET simulations[3] and the Coding to Learn and Create resource toolkit[4] are great ways to inject active, experiential and self-directed learning in a remote environment.

Equip students to become experts in their own learning and to self-advocate for what they need; encourage them to take risks and make mistakes, and to value their individualised progress. Ways to foster these skills in a learning environment include the following:

- Throughout the learning process, have many points of reflection that encourage students to consider why they are learning something; to examine strategies they used to complete a task and to assess their level of engagement.

- Use alternatives to standard evaluation, including conversations and written feedback not associated with a grade, or peer and self-assessment to further develop participation, collaboration and personal development.

- Create environments that celebrate risks and mistakes by encouraging students to try new or different approaches to see what works best for them. Build opportunities for students to redo tasks or assignments to foster creative risk-taking.

The Value of Open Education

Open education is an ideal environment for building diverse choices. Resources that reside in an open digital environment (open educational resources, or OER for short) are flexible and amenable to change and can be adapted, remixed, built upon or modified for use by the global learning community. Open education offers a global learning community that supports the collective production of a range of learning resources to meet a given learning goal for a range of learning needs. This alleviates the demand on individual educators to meet all the needs on their own. Time and other resources spent to make materials accessible and inclusive are not redundantly repeated by each teacher. Class learning goals can be achieved through many different approaches that match individual learning needs.

Learners can also contribute to educational materials. When their efforts are harnessed, learners can become active participants in the learning community and gain a sense of purpose and empowerment. Scaling inclusivity in the learning environment can be easier when we move learners away from a passive-receiver learning model and engage them in the active creation, sharing and assessment of knowledge with peers.

Open education learning communities and OER can be found through many channels. A list of OER can be found on SNOW (/the-inclusive-classroom/open-educational-resources/find-an-oer/).

Conclusion

In any given learning environment, one constant is that every student is different. The differences students bring to a learning environment offer diversity in thinking, ways of being, and ways of learning and progressing — all qualities to be harnessed for an innovative and resilient way forward, both individually and collectively. Optimising each student’s learning potential requires a broad range of choices and a change in our attitude to diversity — stretching our design of learning to encompass the unexplored 80 per cent of the learning terrain occupied by the currently excluded 20 per cent of the learners. To optimise learning for the large range of diversity in any class is a daunting task for teachers, but open pedagogy and OER can help. A global, connected learning community that engages students to create and expand the range of choices will serve learning and inclusion goals.

To achieve and sustain equity requires change at all levels of education. This moment of disruption —the awareness that our future is entangled in many connected systems, is complex in its contextual uniqueness, and is forever unpredictable — may provide the impetus to employ more-inclusive practices.

Annex: Resources

Toolkits

FLOE, Flexible Learning for Open Education: https://floeproject.org/

Inclusive Learning Design Handbook: https://handbook.floeproject.org/

Microsoft Inclusive Design: https://www.microsoft.com/design/inclusive/

Open Text BC Accessibility Toolkit: https://opentextbc.ca/accessibilitytoolkit/

Co-design Resource

The Inclusive Design Handbook: https://guide.inclusivedesign.ca/practices/PracticeCoDesign.html

Inclusively Designed Resources

Coding to Learn and Create: https://www.codelearncreate.org/

PhET: https://phet.colorado.edu/en/accessibility/prototypes

Individualisation Tools

Clusive: http://cisl.cast.org/products/about-clusive

User Interface Options: website https://floeproject.org/ui-options.html; Chrome browser extension https://floeproject.org/news/2018-01-31-uioPlus.html

Open Education

Inclusive Design for Learning: An educator’s guide to Open Educational Resources (OER): https://www.oercommons.org/courseware/lesson/69462

Merlot: https://www.merlot.org/merlot/

OER Commons: https://www.oercommons.org/

Open educational resources and the inclusive classroom: /the-inclusive-classroom/open-educational-resources/

Open Pedagogy: https://open.bccampus.ca/what-is-open-education/what-is-open-pedagogy/

Open Textbook Library: https://open.umn.edu/opentextbooks

Accessible Education Material and Media

Accessible Digital Office Document Project (ADOD): https://adod.idrc.ocadu.ca/

Accessible Education Material and Media: /accessible-media-and-documents/

Alternative text (from WebAIM): https://webaim.org/techniques/alttext/

Amara video captioning. Use Amara’s technology to caption and subtitle any video for free: https://amara.org/en/

Pressbooks — book writing software that enables people to create books in all the formats needed for publishing: https://pressbooks.com/

References

Center for Applied Special Technology (CAST). (2020). About Universal Design for Learning. http://www.cast.org/our-work/about-udl.html#.X0WyMed7laR

Inclusive Design Research Centre. (2020). What is inclusive design? https://idrc.ocadu.ca/

Saebones, A. M., Bieler, R. B., Baboo, N., Banham, L., Singal, N., Howgego, C., McClain-Nhlapo, C. V., Riis-Hansen, T. C., & Dansie, G. A. (2015). Towards a disability inclusive education: Background paper for the Oslo Summit on Education for Development. https://atlas-alliansen.no/publication/towards-a-disability-inclusive-education-2/

Treviranus, J. (2018). The three dimensions of inclusive design: Part one. Medium.com. https://medium.com/fwd50/the-three-dimensions-of-inclusive-design-part-one-103cad1ffdc2

Wikipedia contributors. (2020a). Pareto Principle https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Special:CiteThisPage&page=Pareto_principle&id=967358099&wpFormIdentifier=titleform

Wikipedia contributors. (2020b). Universal Design for Learning. Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Universal_Design_for_Learning&oldid=963236138

Bibliography

Balliester, T., & Elsheikhi, A. (2018, March). The Future of Work: A Literature Review [Research Department Working paper No. 29, International Labour Office]. https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—dgreports/—inst/documents/publication/wcms_625866.pdf

Choo, S.S. (2020). Examining models of twenty-first century education through the lens of Confucian cosmopolitanism, Asia Pacific Journal of Education, 40:1, 20-34, DOI: 10.1080/02188791.2020.1725435

DeRosa, R., & Jhangiani, R. (2019, March 30). Open Pedagogy. http://openpedagogy.org/open-pedagogy/

Downes, S. (2019, November 4). A Distributed Content Addressable Network for Open Educational Resources. https://www.downes.ca/post/70094

Guglielmino, L. M. (2013, October). The Case for promoting Self-Directed Learning in Formal Educational Institutions [PDF]. South Africa: SA-eDUC Journal Volume 10, Number 2. http://www.nwu.ac.za/sites/www.nwu.ac.za/files/files/p-saeduc/sdl%20issue/Guglielmino%2C%20L.M.%20The%20case%20for%20promoting%20self-directed%20lear.pdf

Treviranus, J. (2020, February 22). Machines are Rule-bound and Standardized, Our Students Need to be More than Machines. https://medium.com/@jutta.trevira/machines-are-rule-bound-and-standardized-our-students-need-to-be-more-than-machines-d5870ee03d0b

Treviranus, J. (2020, June 25). Preparing a next generation that understands the value of human diversity and can navigate. https://medium.com/@jutta.trevira/preparing-a-next-generation-that-understands-the-value-of-human-diversity-and-can-navigate-2aacf66381eb

UN News. (2019, June 10). The future of work ‘with social justice for all’ tops agenda of centenary UN Labour conference | | UN News. Economic Development. https://news.un.org/en/story/2019/06/1040161

Vander Ark.T. & Schneider, C. (January 22, 2014). Deeper Learning for Every Student Every Day. Hewlett Foundation. https://hewlett.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/Deeper%20Learning%20for%20Every%20Student%20EVery%20Day_GETTING%20SMART_1.2014.pdf

Wikipedia contributors. (2020). Knowledge Building. Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Knowledge_building

Wood, J. (2018, October 11). Children in Singapore will no longer be ranked by exam results. Here’s why. https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2018/10/singapore-has-abolished-school-exam-rankings-here-s-why?utm_source=Facebook+Videos

Woods, D.R. (1996). “Problem-based Learning: resources to gain the most from PBL,” Waterdown, ON, ISBN 0-9698725-2-6, https://www.eng.mcmaster.ca/sites/default/files/uploads/pbl-book-appendix-a.pdf

Colophon

The Commonwealth of Learning (COL) is an intergovernmental organisation created by Commonwealth Heads of Government to encourage the development and sharing of open learning/distance education knowledge, resources and technologies. COL is helping developing nations improve access to quality education and training.

INCLUSIVE DESIGN FOR LEARNING: CREATING FLEXIBLE AND ADAPTABLE CONTENT WITH LEARNERS

This guide was prepared by Caren Watkins, Dr. Jutta Treviranus, and Dr. Vera Roberts of the Inclusive Design Research Centre (IDRC) at OCAD University, Ontario, Canada

Critical Readers: Gareth Dart and Dr. Betty Ogange

Copy Editors: Natalia Angheli-Zaicenco and Dania Sheldon

Designer: Ania Grygorczuk http://oasis.col.org/discover

The Knowledge Series is a topical, start-up guide to distance education practice and delivery.

New titles are published each year. Also available at http://oasis.col.org.

All Web references and links in this publication are accurate at press time.

Commonwealth of Learning, 2020

Commonwealth of Learning, 4710 Kingsway, Suite 2500, Burnaby, BC

V5H 4M2, CANADA PH: +1.604.775.8200 | FAX: +1.604.775.8210

E-MAIL: info@col.org | WEB: www.col.org

[1] Global accessibility guidelines most often referred to include: Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG), which support content that can be adapted and does not have barriers; User Agent Accessibility Guidelines (UAAG), which support viewing and interacting with the content; and Authoring Tool Accessibility Guidelines (ATAG), which ensure (i) that people with disabilities can be producers and not just consumers of content and (ii) the creation of WCAG-compliant content by default.

[2] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Problem-based_learning